five

a book, a song, a prayer, a photo booth, a thought about product management and a remembrance of times past in the magazine industry

one: 253 by Geoff Ryman

In 1998 I was working in the City of London (where, after a 25-year gap, I find myself working again now) and spent a fair amount of time in the bookshops of the square mile, all of which are now gone. There used to be a whole funny little district of booksellers and bookbinders in a warren of alleys leading into Paternoster Square behind St Paul’s Cathedral. The newly developed Square, with its repositioned Temple Bar gate and semi-tasteful restaurants, is probably an improvement, all told, but is not as conducive to good reading.

One of the books I picked up largely because its cover appealed to me, was a slim paperback called 253 which turned out to be by a Canadian science fiction writer called Geoff Ryman. It was an experimental novel - my first foray into reading experimental fiction, which would later take me into the path of one of the form’s masters, BS Johnson, but he is for another time. The book tells the story of 253 people travelling on a southbound Bakerloo Line tube train one day in January 1995.

Ryman had originally made it as a piece of interactive fiction for what was then the new technology of the World Wide Web. The site was unavailable for years, but it was brought back by Ryman a few months ago for the anniversary of the book. It is excellent and you should read it (or if you’ve already read it, read it again).

two: harbinger customers

I learned about this concept a few years ago and I still find it fascinating: if you’re in the business of building or creating products - as I am - there are always customers whom you wish to court, be they influencers (of whatever kind) or big-name clients or people whose needs are most obviously unmet.

But there is a second type of customer whom you probably want to avoid: the harbinger customer. There’s a good 2020 New York Times article on them which outlines the idea: that there is a type of person who is drawn to products that are doomed to fail. And what’s strange is that not only do these harbingers’ tastes predict failure in one product, but one harbinger can predict taste in many types of product. And stranger still, the effect applies even to regions and areas - a paper published by MIT in 2019 suggested that harbinger ZIP codes exist, in which more people than average make these unusual purchasing decisions compared with households in other areas. And they even predict losing electoral candidates. One Reddit user even claimed to have worked backward from the paper and identified the localities in question:

Now, we’re firmly in the realm of social science, which is in the middle of a massive replication crisis, so it’s entirely possible that this will all turn out to be complete nonsense. And it’s not possible to just walk up to one of these harbinger customers and ask them to tell you what they think of your product, so the idea is of little practical use, but it’s an interesting one nonetheless. If there are people who can pick out winners, it’s not far-fetched to believe that there are people who unfailingly pick out losers.

three: Dexy’s Midnight Runners

My son and I were recently listening to Come On Eileen by Dexy’s, and I noticed that last year the band released a remixed version (in the original meaning of ‘remixed’) which is an interesting comparison, and apparently closer to what Kevin Rowland wanted to achieve in 1982. Both videos below:

four: Prayer, by Carol Ann Duffy

A propos of nothing, I was recently reminded of Carol Ann Duffy’s poem Prayer

Prayer

Some days, although we cannot pray, a prayer

utters itself. So, a woman will lift

her head from the sieve of her hands and stare

at the minims sung by a tree, a sudden gift.

Some nights, although we are faithless, the truth

enters our hearts, that small familiar pain;

then a man will stand stock-still, hearing his youth

in the distant Latin chanting of a train.

Pray for us now. Grade 1 piano scales

console the lodger looking out across

a Midlands town. Then dusk, and someone calls

a child's name as though they named their loss.

Darkness outside. Inside, the radio's prayer -

Rockall. Malin. Dogger. Finisterre.

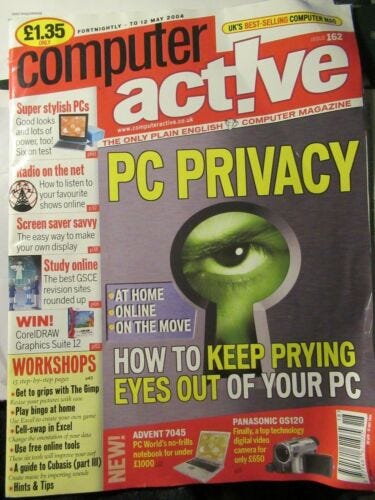

five: the end of computer magazines

Harry McCracken writes about the final print editions of two American computer magazines, Maximum PC and Mac Life. I spent my teens reading computer magazines and music magazines, and my twenties writing for them, and so it was with some sadness that I read Harry’s reflections on the death of print computer magazines in the USA.

I left computer magazines in 2011 having become convinced that audiences were no longer interested in what we had to offer them, and that the barrier to entry was low enough that - to take an example from my particular line of work, editing a reviews section - anyone could either buy software or hardware off the shelf and write a review of it, or they could increasingly convince tech companies’ PR departments to send them the same review samples that we’d been getting, on the basis of growing web traffic that the old print dinosaurs hadn’t been able to capitalise upon*.

The picture below is of issue 121 of Computer Shopper, in its 1998 heyday. Issue 121 has, including the advertising, nearly 1,000 pages, and always felt like the Bible, not just because of its heft but also because of the thinness of its pages. As Harry says, this style of catalogue-magazine was always going to be hit hard by the advent of shopping on the web.

As the chart below shows, I was actually fairly slow on the uptake: by 2011 the computer magazine sector in the UK (the chart shows the biggest titles in the market between 2000 and now, and it’s striking that only two of those titles are left standing) had already taken most of the damage it was going to, and the 12 years after that were really a period of retrenchment and finding of whatever stability they could in the new, much smaller world in which they found themselves.

The prior ten years were where all the damage happened, and to be honest, it did feel like that at the time. It wasn’t fun being in the quarterly editorial meetings in which the story was always and inevitably one of decline, in which if we were bucking the rest of the market by declining more slowly than our competitors, then we took that to be a victory. It’s not until you see the decline mapped out as starkly as it is in the graph that it becomes clear quite how badly things were falling at that time, even for what was still then the biggest-selling technology publication in Europe. In total, for those six titles, the total circulation fell from 841,000 in 2000 to just 79,000 today, just slightly more than one of the smaller titles, PC Gamer, was selling per issue in 2000.

What is surprising, looking back, is not just the number of people the magazine healthily supported - journalists including writers, editors and sub-editors (both freelance and staff), designers, sales people, brand and marketing, print and process, lab technicians, photographers and illustrators to name a few - but that they were being supported at wages and rates that, if not exactly lavish in 2004, look positively generous by the standards of what people get paid for writing and other work online in 2023 (with a tiny number of exceptions such as Vittles).

*the star is because at the time, and for several years after 2011, it did look like those old print dinosaurs weren’t able to build web audiences, but there has in the last couple of years been one apparent British success story, which is Future Publishing. Having bought out several of the other major magazine publishers in the UK (IPC, which was itself part of Time Inc by the time of its surrender, Dennis, and parts of my own former employer VNU-Ziff Davis which had ended up with Dennis at various points over the last 20 years) Future has now been able to build a remarkably stable and growing business of digital titles.

six: AI photobooth

A Reddit user has turned an old telephone exchange switchbox into some sort of AI photobooth. I’ve no real idea what it’s doing, but I like the steampunk innovation.

I am sort of a harbinger customer. Not completely and not in everything, but my tastes in certain things are just not going to line up with the big market you are looking for.