Remembering Leo Marks

One of wartime Britain’s brightest minds was born one hundred years ago today

The owner of one of wartime Britain’s brightest minds was born one hundred years ago today

Leo Marks was born on 24 September 1920, which means that today would have been his hundredth birthday. In all the (appropriate) celebration of Alan Turing, it sometimes feels as though we forget that Turing was not a sole genius (genius though he was) who cracked the German wartime codes alone. There were others, both at Bletchley Park and beyond, who did extraordinary and ground-breaking work on codes, some of which, like Turing’s work, paved the way for the modern information age. Leo Marks was unquestionably one of those people.

I’ve been fascinated by Marks ever since I read about him in the excellent London Compendium by Ed Glinert (Penguin, 2004). In that book, a collection of snippets of different parts of central London, Glinert describes how Marks turned up one day in 1942 at an interview session for prospective code breakers.

He was given a section of encrypted message and ordered to break it (to translate it into readable English), and duly set to work. When he failed to break it within the allotted 20-minute time limit, he asked for more time and was given it out of pity. He took the rest of the day to break the code and, assuming himself a dimwit, handed the cracked message in at 4.45pm to the commanding officer, Captain Dansey, the head of codes:

At a quarter to five I knocked on the door of Dansey’s office and put the decoded message in front of him. Dansey and Owen [Dansey’s deputy, Lieutenant Owen] sat in silence. They were in mourning for their judgement. They knew I had failed and hoped it wouldn’t prevent them from giving someone competent a chance. I thanked my ex-bosses for my tea and turned to go.

‘Leave the code here, please.’

‘What code, sir?’

Dansey closed his eyes but they continued glaring. ‘The code you broke it with!’

‘You didn’t give me one, sir.’

‘What the hell are you talking about? How did you decode that message if I didn’t give you one?’

‘You told me to break it, sir.’

He was one of those people who could look efficient with his mouth open. ‘You mean you broke it,’ he said, as if referring to his heart, ‘without a code?’

I had always understood that was what breaking a code mean, but this was no time for semantics. ‘How was I expected to do it, sir?’

‘The way the girls do, with all the bumph in front of them. A straightforward job of decoding, that’s all I was after! So we could test your speed. And compare it with theirs.’

‘You mean, sir — that SOE is actually using this code?’

‘We were,’ said Owen. ‘We have others now.’

They looked at each other. Something seemed to occur to them simultaneously. They operated like two ends of a teleprinter.

‘Come with us, Marks.’

SOE was the Special Operations Executive, a secret branch of government that had been created in July 1940 with a mandate to conduct sabotage and espionage in occupied Europe. Its members were sometimes known as “Churchill’s Secret Army” or the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare”, and Churchill himself is said to have told SOE to “set Europe ablaze”.

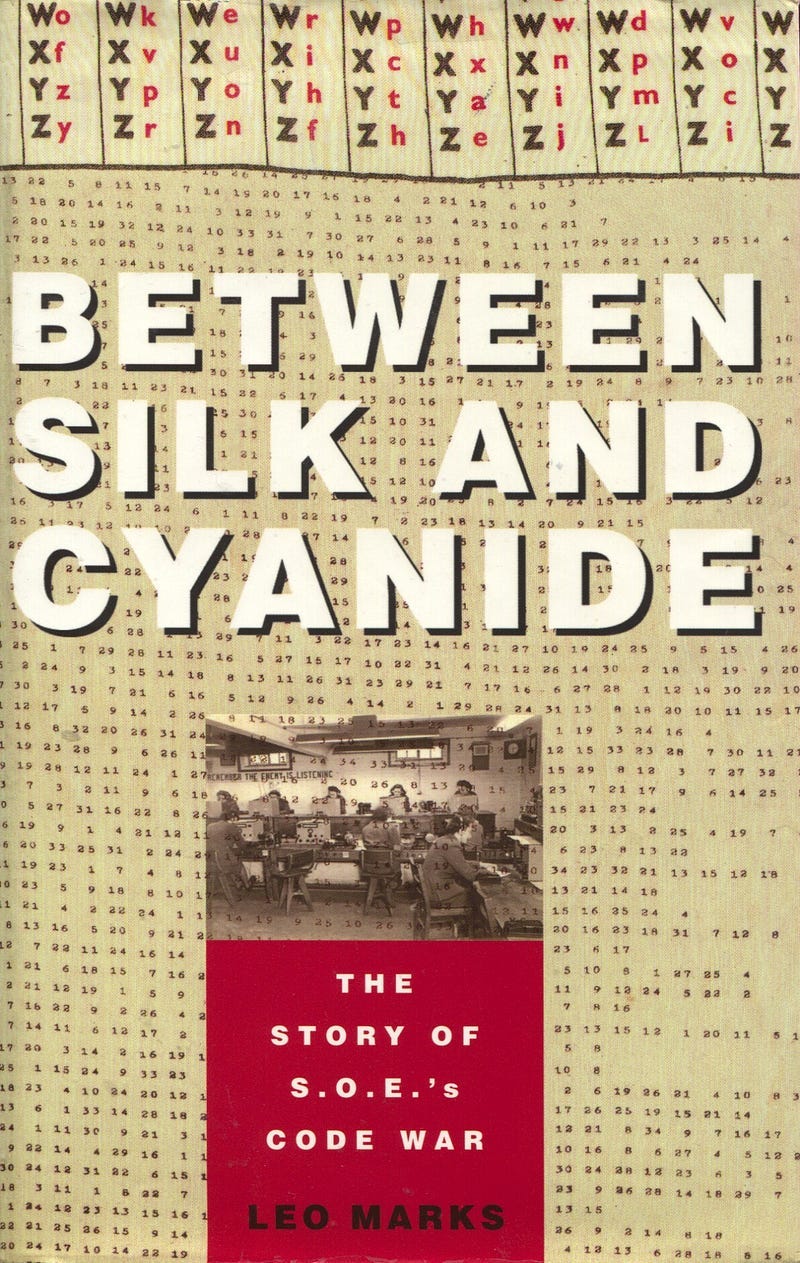

Codes were hugely important to SOE, allowing London to maintain contact with its field agents under strict secrecy. Marks’s book Between Silk and Cyanide (HarperCollins, 1998), from which the above excerpt is taken, is a thoroughly entertaining recollection of his years at SOE, beginning when he was only 21 years old.

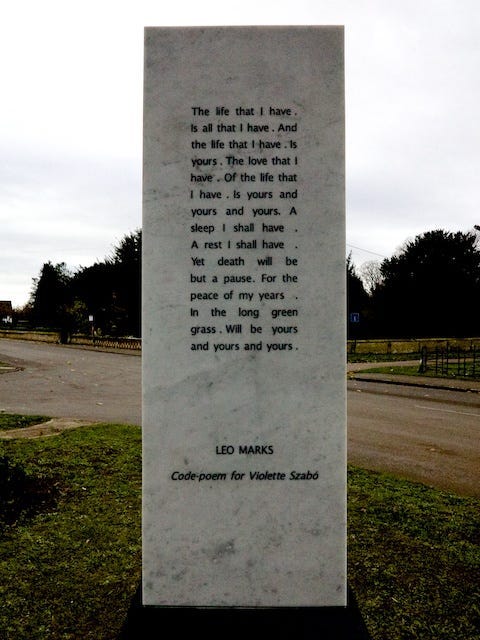

Among Marks’s many creations were several “code poems”, original works by him which agents would memorise and use as the basis for their encrypted transmissions from the field. The ones reprinted in the book rise well above the level of doggerel. Marks also came up with two startling inventions that may have saved enormous numbers of agents’ lives: worked-out codes, and letter one-time pads, which he endearingly refers to as LOPs and WOKs.

From the very first sentences, it fizzes along: “In January 1942 I was escorted to the war by my parents in case I couldn’t find it or met with an accident on the way. In one hand I clutched my railway warrant — the first prize I had ever won; in the other I held a carefully wrapped black-market chicken.”

In the days when prospective writers occasionally asked for my advice, I would often tell them that in order to become better writers they should read as much and as widely as possible. Leo Marks grew up surrounded by books — his family being the owners and proprietors of one of the city’s most famous bookshops, Marks & Co at 84 Charing Cross Road — and he seems to be an exemplar of the benefits of reading often and widely. His deft literary touch makes the book fly by, from its lightest moments to its most serious.

After the war SOE was more or less absorbed into MI6, against what Marks tells us several of his colleagues wanted. He himself stayed only as long as it took to clear up his department’s affairs. He later became a playwright and screenwriter, writing among other things the controversial 1960 Michael Powell film Peeping Tom, a later favourite of Martin Scorsese. Leo Marks died in January 2001.

Here’s another excerpt, from the book’s epilogue:

A film was made about Violette Szabo called Carve Her Name with Pride, and I allowed its producer, Daniel Angel, to use the poem [pictured above] in his film providing that its author’s name wasn’t disclosed. Thousands of letters poured in asking who’d written it and the Rank Organization professed not to know but felt they should send me a letter they’d received from the father of an eight-year-old boy. He said that his son was desperately ill, and could someone please answer the enclosed letter, which was written in code.

I managed to break his baby code, and the clear-text read: ‘Dear code-master. She was very brave. Please how does the poem work, I’m going to be a spy when I grow up.’

I replied to him in his code (this was essential), saying that as soon as he was better of course I’d show him how it worked. And as soon as he was better he might like to come to the Special Forces Club and meet some of the other agents he might have read about. In the meantime I was sending him a chess-set which Violette once gave me because I knew that she’d like him to have it.

Six weeks later I received a letter from his father saying that his son had rallied for a month, and had died with the chess-set and the poem on his bed.